This article needs additional citations for verification. (April 2021) |

Tibor Sekelj (14 February 1912 – 23 September 1988[1]), also known as Székely Tibor according to Hungarian orthography, was a Hungarian[2] born polyglot, explorer, author, and 'citizen of the world.' In 1986 he was elected a member of the Academy of Esperanto and an honorary member of the World Esperanto Association. Among his novels, travel books and essays, his novella Kumeŭaŭa, la filo de la ĝangalo ("Kumewawa, the son of the jungle"), a children's book about the life of Brazilian Indians, was translated into seventeen languages, and in 1987 it was voted best Children's book in Japan.[3] In 2011 the European Esperanto Union declared 2012 "The Year of Tibor Sekelj" to honor the 100th anniversary of his birth.[4]

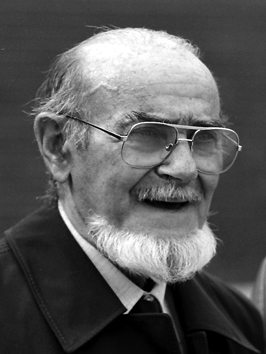

Tibor Sekelj | |

|---|---|

Tibor Sekelj in 1983 | |

| Born | 14 February 1912 Georgenberg (part of Poprad), Austria-Hungary |

| Died | 23 September 1988 (aged 76) Subotica, Yugoslavia |

| Occupation | writer, lawyer, explorer, Esperantist |

| Citizenship | Yugoslavian |

| Education | lawyer |

| Alma mater | University of Zagreb |

| Period | 1929–1988 |

| Genre | Esperanto literature |

| Notable works | Kumeŭaŭa, la filo de la ĝangalo (1979) Tempesto sur Akonkagvo, La trovita feliĉo, Tra lando de Indianoj, Nepalo malfermas la pordo (Window on Nepal), Ĝambo Rafiki, Mondmapo, Padma, Mondo de travivaĵoj, Elpafu la sagon, Neĝhomo, Kolektanto de ĉielarkoj; See bibliography |

| Spouse | Erzsébet Sekelj |

Biography

editYouth 1912–1939

editSekelj's father served as a veterinarian in the Austro-Hungarian Army and as a result the family moved around extensively. Several months after Tibor's birth the family moved to Cenei (now in Romania), where Tibor lived until he was ten years old. While Hungarian was his "mother tongue", the commonly spoken language was German. Sekelj had at least two sisters and a brother, Antonije, who later collaborated with him on several books. In 1922, the family settled in Kikinda, part of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia (now in Serbia), where Tibor learned Serbo-Croatian. He also studied French and soon was teaching it to his fellow students. Sekelj went on to learn a new language every four years. In 1926 his family moved to Nikšić (now in Montenegro), where he took up gym, mountaineering and where he walked the entire length of Montenegro. In 1929 he entered the University of Zagreb (in Croatia) and in 1933 was one of the three youngest students to have graduated from the school of law. During that time Tibor also studied painting, sculpture, Esperanto, filmmaking and journalism. But the practice of law bored him, and he turned his attention to writing. He began working as a journalist in Zagreb. In 1937 he started to work in Zagreb as a film screenwriter. In 1982, in Leuven, Belgium, at the World Youth Esperanto Conference, he discussed his Sephardic Jewish ancestry with Neil Blonstein.

World traveler

editStarting in 1939, Sekelj was a tireless globetrotter, and while he always returned to Serbia in between his many journeys, his need to explore new horizons melded with an insatiable curiosity about people. His travels and expeditions yielded books that have been translated into over twenty languages.

- Trips goals

- Themes of books

- Homeland

- European countries

South America 1939–1954

editIn 1939 he left Zagreb for Argentina to write an article on Croat exiles for a Zagreb newspaper Hrvatski Dnevnik. Sekelj was on the ship Teresa[5] on what might have been that ship's last voyage due to the start of World War II. In 1939 the other ships that normally traveled to South America from Rijeka-Fiume were being used by Italy due to the war in Africa. Setting sail from Rijeka (then Fiume in Italy), he headed for Buenos Aires, with stops in Naples, Genoa (Italy) Santos (Brazil), and Montevideo (Uruguay). Tibor reached Buenos Aires on 19 August 1939. A pacifist by nature, Sekelj had anticipated the outbreak of war and so chose to be far from the fighting. This difficult decision was due not to a lack of personal courage—Sekelj was known to display almost foolhardy bravery throughout his life—but because this Jewish Hungarian/world citizen was simply unwilling to hew to any ideology tied to military purposes.

Within two years[6] he had honed his knowledge of Spanish and got work as a journalist, publishing a monthly magazine dedicated to travel and exploration. Sekelj remained in Argentina for the next 15 years, writing and exploring South America.

1939–1945: Argentina, Aconcagua

editIn 1944, with no prior mountaineering experience, Sekelj joined a crew on an ascent on Aconcagua, the highest mountain (6,962m) in the South American continent.,[7] led by the Swiss German mountaineer Georg Link. Sekelj, the Austrian Zechner and the Italian Bertone reached the summit on 13 February 1944. But tragedy loomed: Four of the six men on that climb perished in a snowstorm. This terrible experience inspired Sekelj to write his first book: Storm Over Aconcagua, which recounts the drama in thrilling detail. On a second climb—initiated by the Argentinian Army, which Tibor led—the corpses of the four young men were found and brought home. As a result, Sekelj added a chapter to the second edition of Tempestad sobre el Aconcagua, 1944 in which he describes that adventure. Then Argentine President Juan Perón personally tried to award Sekelj honorary Argentine Citizenship for his actions, along with the Golden Condor the country's highest medal of honor. Tibor, in his gentle rejection of the offer of citizenship, stated that, while he deeply appreciated the offer, as a Citizen of the World, he could not be bound to any one country.

1946–1947: Mato-Grosso

editBased on the success of his first book, Sekelj's publisher urged him to write a second, unrelated one. With a budget of two thousand dollars, Sekelj chose to explore uncharted regions of the Brazilian rainforests in Mato Grosso, otherwise known as the River of Death. In 1946 he undertook first of two expeditions into the Amazon jungle, which produced a popular book, "Along Native Trails" (Por Tierra De Indios). His partner on this arduous journey was an Argentinian of Russian descent Mary Reznik (1914–1996). Together they spent nearly a year exploring tribes along the Araguaia and Rio das Mortes Rivers. Along the way they survived contact with the fearsome Xavantes Indians, who had killed over a hundred people, in many expeditions before them. They also encountered the Karajá and Javae Indians on this expedition. Eventually the book Por Tierra de Indios (1946) chronicling survival in difficult circumstances, amid illness and near-starvation, met with great success, was reprinted repeatedly and translated into many languages. In 1946 Tibor and Mary married. Together they returned to the Amazon in 1948. After that expedition he penned "Where Civilization Ends" (Donde La Civilizacion Termina).

In the summer of 1946, Tibor traveled through Patagonia with three companions : Zechner, Mary and Dr Rosa Scolnik. During the following years he audited classes at the University of Buenos Aires to attend lectures on anthropology, ethnology and archeology, in order to get useful knowledge for his upcoming expeditions.

1948–1949: Bolivia, Jivaros

editIn 1948 a failed expedition to find the Jivaros led Tibor and Mary to Bolivia, where they met with President Enrique Hertzog. He encouraged them to explore the unknown area of the River Itenez, which abuts with Brazil. During that difficult six-month-long journey they encountered more hardships and hostile Indians, among them the Tupari, a tribe that only a few years before had been practicing cannibals. In April 1949, President Hertzog of Brazil proposed that Sekelj should oversee a territory spanning one hundred thousand hectares, from the planned 4 million hectares meant to house a million European refugees. Sekelj, rather than having to wait for six months for parliament to render a decision, turned down the offer. He later regretted the missed opportunity to have a place where Esperanto could become the common language to its populace.

1949–1951 Venezuela

editAfter attending the World Congress of Esperanto in UK, Tibor spent seven months in Europe. He returned to South America, joining Mary in Venezuela. For the next seventeen months he wrote newspaper articles, while managing a musical instruments store in Maracaibo. After going to Caracas to oversee the creation of a series of historical murals, he began traveling through Central America on his own, as by this time he and Mary and separated. The couple formally divorced in 1955, and soon after Mary went to the United States, where she remarried. Their son, originally named Diego after a son of Christopher Columbus, took her second husband's surname. Daniel Reinaldo Bernstein as of 2011[update] is a respected acupuncturist and musician living in New York City.

1951–1954: Central America

editTibor later wrote about being on the island of San Blas in Panama, where he engaged with the Kuna Indians; of an attempt to scale the volcano Izalko in El Salvador, that was cut short by a volcanic eruption; and of discovering the ruins of an ancient city in Honduras, which many people knew from legends only, and that was built by Indians. It was during these treks through Guatemala and Honduras that Sekelj became ever more immersed in archeology and anthropology.

Upon Sekelj's arrival in Mexico in 1953, several alpine clubs invited him to take part in their treks. This was not unexpected, given the fact that his book « Tempestad sobre el Aconcagua » had practically become a manual for mountain climbing. He climbed Popocatépetl, Iztaccihuatl and many other volcanoes and mountains, further firming up his expertise in that arena. One of many fascinating explorations at that time was the underground crossing of the river San Heronimo, lying 14-km within the interior of mountain.[8]

Subsequent world trips based from Europe 1954–1988

editIn 1954 Sekelj returned to his home in Belgrade, Yugoslavia. He was given a warm welcome by the local government and its people, as much for his humanitarian message as for his fascinating travelogues. Along with his countless newspaper articles, his books were translated into Serbian, Slovenian, Hungarian, Albanian and Esperanto. He continued to travel and write of his experiences.

1956–1957: India, China, Nepal

editIn 1956 he drove through Asia as a World Esperanto Association (UEA) observer to an upcoming UNESCO talk held in New Delhi. When his car crashed in Tehran he continued on by bus and rail. During that journey he met extensively with Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru and his daughter, future prime minister Indira Gandhi. He also befriended the future president Dr Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan. In the Yugoslav embassy he met with Ljubomir Vukotić, then president of the World Federation of the Deaf When Vukotić met with Indian and Chinese representatives to open an Asian office, Seklelj acted as interpreter, bridging a communication gap between non-hearing people of different languages. In January 1957, he accompanied Vukotić to China, which at the time was not accepting visitors. This was followed by a six-month stay on the invitation of King Mahendra of Nepal, another country that was, at that time, hostile to foreigners. King Mahendra personally thanked Sekelj for founding the first people's university, and for helping to spread the teaching of Esperanto.[9] This friendship is in part the subject of Tibor's book, « Nepal opens the door », 1959, which he first wrote in Esperanto while in Madras studying yoga philosophy. The book was translated into multiple languages, including English, Spanish, Serbian and Slovenian. His journey through India, on foot and by bus, led Tibor from village to village, and from temple to temple, culminating in a month-long stay in a cave with three Yogin.

1958–1960: Vinoba Bhave, Japan, Sri Lanka

editAfter spending six months in Europe Sekelj again flew to India, this time to teach Esperanto to the great Indian Mystic, Vinoba Bhave. The Hindu scholar mastered Esperanto within a month. Sekelj remained in India for five months before landing, penniless, in Japan. In March 1960, he set off on a four-month tour across 30 cities in Japan, always welcome at the home of Esperantists there. Between lecturing and writing newspaper articles, Sekelj earned enough money to buy an airplane ticket to Sri Lanka, and then to Israel before returning to his home base in Belgrade.

1961–1963: Morocco, "Caravan of Friendship" in Africa

editIn 1961, Sekelj accepted the invitation of Moroccan Esperantists and traveled to Morocco, where he joined a caravan of Tuaregs nomads into the Sahara. In March 1962, Tibor set off for Africa on a Karavano de Amikeco (Caravan of Friendship), with eight people from four countries in two all-terrain cars. With a goal of direct communication between people, this yearlong journey reached Egypt, Sudan, Ethiopia, Somalia, Kenya and Tanzania. When a second caravan meant for other African countries failed to materialize, Tibor climbed Mount Kilimanjaro, the highest peak in Africa. This trip is the theme of his book Ĝambo rafiki. Although he wrote the book in Esperanto, it first appeared in Slovene.

1965–1966: Russia, Japan, Mongolia, Europe

editIn 1965, on his way to the World Congress of Esperanto in Tokyo, Tibor traveled by train across Russia (Moscow) and Siberia (Irkutsk and Khabarovsk) to Nahodka, before landing in Yokohama by boat. A month later Tibor crossed Siberia by train, with a side trip to Mongolia. Given the antipathy to foreigners there, his three-month stay was difficult, despite having a stamped visa and correct documents. In ensuing years Tibor Sekelj managed to visit every European country, with the exception of Albania and Iceland.

1970: Australia, New Zealand, New-Guinea

editIn 1970, Yugoslav television sent Sekelj to Australia, New Zealand and New Guinea. During his six-month stay he climbed Mount Kosciuszko[10] In New Guinea he met with natives whose lack of previous contact with the civilized world led to tense situations. But among Sekelj's many skills—and perhaps luck was just another one—was an uncanny ability to escape imminent danger time and again. Certainly he adapted easily to odd customs (including bizarre food), but if there was a single thing in particular that helped in this regard, it was his communication skills, which transcended even his facility with language.

1972–1980: North America, Russia, Uzbekistan, Nigeria, Ecuador

editIn 1972, while at the international congress of ethnologists in Chicago Tibor visited eastern Canada and United States. In 1977, during the same event in Leningrad, he saw Uzbekistan and Central Asia. That same year he took part in a festival celebrating the culture of former slaves in Lagos (Nigeria). In 1978, during an assignment for Yugoslav TV, he returned to South America, where he visited Ecuador and the Galápagos Islands.

What amazed many was how this tireless traveler always got funding for his travels. He famously attributed this ability to the fact that he did the work of seven: Writer; cameraman; assistant; photographer; and buyer and shipper of ethnographic artifacts. While each of these jobs is usually delegated to others, Sekelj was a one-man crew. Of course, one could have added 'Ad Man' to that list. Whenever it was possible, Tibor would wrangle advertising contracts from airlines in exchange for discounted tickets.

Work for Esperanto

editSekelj devoted much of his life to the defense and promotion of Esperanto. A Committee member of UEA since 1946, he sought for over thirty years—with a brief break while skirmishing with Ivo Lapenna) over its activity within the Instituto por Oficialigo de Esperanto (IOE),[11] to be part of all the universal Esperanto Congresses. And as a representative of the IDU—the International Committee for Ethnographic Museums—he took part in numerous conferences. Sekelj's polyglot abilities often assured that he alone could understand all of the multi-national speakers there.

In 1983, he co-founded EVA (Esperantist Writers Association and was its first president. In 1986 he was elected to be a member of the Academy of Esperanto.

He took every opportunity to advocate for Esperanto, particularly in the international Writers association PEN[12] and at UNESCO. In 1985, during the 27th Conference in Sofia, Sekelj was commissioned by UEA to ensure that Unesco would draft a second resolution that would be favorable to Esperanto .

1972–1988: Director of museum in Subotica

editIn 1972, he took a four-year job as head curator of the Municipal Museum in Subotica (Serbia – Vojvodina). In the later 1970s he took advanced studies in museology in Zagreb University leading to a doctorate (in 1976). His innovative ideas and projects found little support, and Sekelj quit his job almost immediately. He attended the World Congress of ethnographers in Chicago in the United States and the World congress of museum professionals in Copenhagen. Upon his election to Secretary of the International Committee of Museologists, he took on various initiatives for new kinds of museums with dioramas.

In 1985, Sekelj met a young woman Erzsébet Sekelj, a librarian, born in 1958, whom he met on a journey through Hungary. That year she learned Esperanto. Sekelj and Erzsébet married in 1987 in Osijek. Together they visited three World Congresses of Esperanto. Erzsébet Sekelj participated in the drafting of the vojvodina organ VELO. They jointly wanted to compile an Esperanto-Serbo-Croatian dictionary, which was never completed due to the death of Tibor.[13]

Tibor lived in Subotica from 1972 until his death, 20 September 1988. He is buried in Bajsko groblje (Baja cemetery) in Subotica, with the highest honors from the city of Subotica. On his grave, under bronze bas-relief one can read that inscription in Esperanto: (WRITER, TRAVELER)

— Gravestone in Subotica[15]

Skills

editTibor Sekelj was adroit at a wide range of skills: journalist, explorer, adventurer, mountaineer, writer, drawer, filmmaker, geographer, ethnologist, museologist, polyglot and actor on the political stage, relating to politicians including aforementioned heads of state. His defense and promotion of Esperanto at Unesco and mainly the UEA. The connecting thread in this man's world view was a consistent access to peoples from around the world.

Geographer

editTraveling certainly helped make him a geographer, but he also was forced to become a true cartographer during his travels. In that regard he researched and designed charts of several previously uncharted parts of South America, especially in Bolivia and Brazil. As a result, a river was named after him: Rio Tibor. He published word maps in Esperanto and edited a professional review «Geografia Revuo» between 1956 and 1964. In 1950 he became a member of Guatemala society about history and geography and, because of his merits in this area, in 1946 the Royal Geographical Society of United Kingdom accepted him as an FRGS.

Journalist

editHe learned about journalism during his student years in Zagreb, where he became a correspondent for Croatian newspapers : one from them, Hrvatski Dnevnik, sent him as his correspondent to Argentina, to do a report on Yugoslav emigrants, which is how he became a traveller. After two years[6] he learned Spanish enough to self-publish, Buenos Aires, in Spanish, monthly organ « Rutas » (Ways) a magazine dedicated to geography, journeys, tourism, explorations, etc.[16]

Working as a journalist for an Argentinian newspaper, he decided to join a planned expedition to Aconcagua, the highest mountain of Americas (more than 7000 m according to contemporary ratings).[7] For the most part he was able to support himself through writing, contributing to many newspapers, mainly in South America and Yugoslavia. In Yugoslavia he contributed to many small newspapers, so that the younger generation learned about Esperanto through his articles in young people's periodicals. In his 60s he became a television journalist, filming a series of TV-reports for the Belgrade Television about the Caravan of Friendship (travel through Africa) for the Zagreb Television about exploring unknown tribes in Australia and New Guinea and for the Novi Sad Television about Bolivia, Ecuador and Peru. He was also a brilliant journalist for Esperanto. Except contribution to many Esperanto-newspapers and organs he was chief editor during 8 years for the Geografia Revuo, E-Gazeto (initially IOE-Gazeto) of 1966–1972 (monthly organ – entirely appeared 65 editions) and VELO during six years (1983–1988 – Vojvodina Esperanto-newspaper).

"Geografia Revuo" appeared between 1956 until 1964,[17] each one volume yearly, except in 1959–1960 neither in 1962. The title-pages of exclusively all six volumes are of Sekelj, only in the 4th issue he left the place of the editorial to Aafke Haverman ("Aviadile tra Afriko") and laid his "Kun la Ajnoj de Hokajdo" in the central booklet. Looked at as entirety, "Geografia Revuo" is virtually personal periodical of Sekelj with some appendices of friends.[18]

He lived chiefly on his work as a journalist (writing articles and stories for many various newspapers and organs) and filmmaker. There were 740 translations of his articles in newspapers and organs.[19] We can say definitely that he was writing for many dozens of newspapers and magazines, mainly in Yugoslavia but also in Hungary, and various countries in South America—not to mention the periodicals in Esperanto. Of the 7500 speeches he gave, the majority centered around his journeys, although he spoke prolifically on many other topics as well.

He traveled through 90 countries and his books appeared in as many countries and a great many languages.[20]

Filmmaker

editTibor's first job after getting his Degree in Zagreb was with a film company, Merkurfilm. The company sent him to learn film production in Prague, where he studied under a famous Czech director Otakar Vávra where for 6 months Tibor studied film direction.

Once Sekelj returned to Yugoslavia in the 1960s, he began getting TV coverage as a journalist. And because his forays into unknown areas required more than just pictures—they required film—Tibor accepted the challenge. He began using his knowledge as a filmmaker, not only directing himself but also using sound and light, camera work and more on his trips to New Guinea and Australia. For Zagreb television he filmed a series of films about those regions and their natives that became a 10-hour-long travel film series seen across Yugoslavia. Amazingly, he did everything on those films alone. In the later part of the 1970s he made films about Colombia and Ecuador where he used a professional team of filmmakers from Novi Sad Television, which promoted his travel films.

He himself was the subject of many interviews, chiefly within former Yugoslav televisions. A large majority of that material has been preserved. One example is an in-depth, two-hour interview with TV journalist Hetrich.[21]

Mountaineer

editIn Argentina he learned about mountaineering with barely enough time to prepare before taking part in an expedition to Aconcagua. Still he was able to survive the climb up that treacherous mountain. Later on, he climbed a number of very dangerous mountains, and on all the continents, between the mountains of Nepal, Mexico and Mount Kilimanjaro in Africa, and Mount Kosciuszko in Australia. His detailed description of the ascent on Aconcagua in a book in Spanish became a sort of textbook for mountaineering in Mexico, and other countries across South America.

Ethnologist

editDuring his travels he became a collector of native masks, hats and musical instruments, along with spoken native poetry. Concerning the latter he published the book Elpafu la sagon, that appeared in Serbocroatian and Esperanto. He donated his tangible collection of masks, instruments and hats to Ethnographic museum in Zagreb and to Municipal museum of Subotica, where most of them were later given to the museum of Senta (Serbia).[22]

Adventurer

editAlthough his goal was never to impress others, the most attractive aspect of Tibor Sekelj's life in the eyes of the public—especially to the non-esperantist—was unarguably his adventurer side. Perhaps it was his ceaseless search to locate the essence of human spirit that led him to remote parts of the earth. Across a span of over forty years he studied, and engaged with, tribes from the rain forests of Brazil and New Guinea, always learning and annotating the customs, lifestyles and philosophies of then unknown peoples in Asia and Africa. Many times he befriended people otherwise hostile to the white man, and often risking his life in the process. He writes eruditely about this in his book in Esperanto "Mondo de travivaĵoj" (The world of experiences ), 1981.

Political militant

editAmong Sekelj's many skills was an ability to create an instant sense of ease between himself and politicians and men in power. Score of heads of state welcomed him into their circle, and in turn he gave them useful advice based on his travels through their territories. During his life he met with various heads of State : From Juan Perón (Argentinian president) he received in 1946 an award, the Golden Condor, along with an offer of Argentinian citizenship due to his bravery on Aconcagua. He met with, and became a friend of, Jawaharlal Nehru (Indian prime minister) and his daughter Indira Gandhi (future Indian prime minister), and with Radhakrishnan (future Indian president). Bolivia president Enrique Hertzog sent him to do research in uncharted regions of Bolivia in 1948, and in 1949 asked him to manage Bolivian territory for European refugees after World War II, offering 100.000 hectares for him to do that. Tibor asked for 4 million, but was told it would take half year for the Bolivian parliament to ratify that. He chose not to wait and left before ratification could take place. Also he met with King Mahendra of Nepal, who thanked Tibor Sekelj for creating the first people's university there, where he taught Esperanto.

The peak of his political activity was in 1985 when he took over the UEA in order to prepare the second resolution of UNESCO on Esperanto. He met with numerous heads of state, ministers and diplomats during his four participations in UNESCO-talks throughout 1984 and 1985. He finally succeeded in convincing the Yugoslavian government to offer that resolution to the Assembly of UNESCO in Sofia, while getting other Esperantists to work on the governments of China, Bulgaria, Hungary, Poland, San Marino and Costa Rica in order to back the resolution. Over the next months he visited the embassies of seven of those countries, finally succeeding in convincing them that they should work with their governments and accept the resolution. In Sofia he negotiated between the delegations of numerous countries to vote on the resolution, which in the end was accepted.

To all of this we can also add the few months he spent living with the Indian philosopher and political activist Vinoba Bhave, not to mention many, many heads of smaller regions and cities and states across the world.

Polyglot

editSekelj learned 25 languages and countless dialects, of which he retained nine at the end of his life: Hungarian, Serbian, German, Esperanto, Italian, English, French, Spanish, Portuguese. Of these he wrote extensively in Spanish, Esperanto and the Serbo-Croatian, He was an interpreter on his travels and as part of his work for PIF[23] during acceptances, arrangements etc.

I learned around 25 of languages. Many of them I forgot, because I stopped using them. I still can use some 9 languages, and although that's not enough to get by in the entire world, I can communicate with almost anyone despite that.

— Interview with Stipan Milodanoviĉ[24]

Esperantist

editAfter becoming an Esperantist in Zagreb in 1930, Sekelj remained committed to the ideals of the international language throughout his life. His contributions to the language are immense: Sekelj founded ten Esperanto-Associations in South America and Asia and Esperanto-societies in 50 of cities across the world.[25][26]

For over twenty years Sekelj was a committee member of UEA and he was single-handedly responsible for the second resolution where UNESCO positively addressed Esperanto in 1985. One-third of his books were originally written in Esperanto. He wrote a great many lucid and cogent articles for various Esperanto-newspapers and magazines, and he drafted Geografia Revuo, E-Gazeto and Velo. But his intense activity in the name of Esperanto related to his foundation and guide of International Institute for Officialization of Esperanto (IOE)[11] that launched the motto « better practice than 100-hours sermon » like this requiring more open activity of Esperantists. In that sense he especially engaged in diverse travel, organizing bus caravans that traveled across the world, having its greatest impact at the start of the International Puppet Theatre Festival (PIF) in Zagreb and later at the foundation for Internacia Kultura Servo (International Cultural Service). PIF still exists, currently after 44 years and still distributes an annual prize "Tibor Sekelj" for the most humanitarian message. His very intensive activity in the name of IOE had a strong effect on the classical neutral Esperanto-movement in the practical application, on the one hand in terms of culture and tourism and on the other to a more elastic conception of impartiality that followed TEJO.

His motto for success: "Three things are essential for success: precisely define your goal, move steadily toward it, and persist until you have reached it."

Teacher

editHe influenced the teaching of Esperanto, and was behind the launching of the first televised course in Esperanto in China. In the 1980s, he wrote textbooks.[27] The authors were A. and T. Sekelj and Klas Aleksandar and Novak Koloman did the illustrations. The course existed also in form of transparencies – actually movies – one can project. He led many Master Esperanto classes wherever he travelled and also took part in the improvement of the «Zagreb method» textbook. Tibor Sekelj gave between 7000 and 8000 speeches, most often with photos of his travels, wrote innumerable articles about Esperanto in the national press and was interviewed hundreds of times for national radios, newspapers and television. He always spoke about Esperanto.

World view

editWherever he was, in his lectures and activities he conveyed to his audience his simple philosophy of life: man as an individual is the most precious thing in his own environment, regardless of descent or education. (This is most clearly expressed in his work "Kumeŭaŭa".) Man as a cultural capital is the product of all humanity, because in our daily lives we interact with products invented by diverse people; he illustrated this with a dining table, explaining that each piece of tableware was invented by a different people, each of the foods that had been developed and planted by different people, and now ten cultures are involved in setting a table. Therefore, every man was a respectable person, and what we have today is the result of efforts of all nations, and therefore belongs to all.

Artist

editAside from being an adept writer, Sekelj studied painting and sculptor while still a student in Zagreb. When he first landed in Argentina, he survived doing portraits and later he often illustrated his own books.

Writer

editTibor is perhaps the most well-known original Esperanto-writers among the non-esperantist world, given the number of his translated books from Esperanto. The most successful his work Kumewawa – the son of jungle has been translated multiple times, while others books have between two and ten translations. Writing in Esperanto, Spanish and Serbo-Croatian he produced some thirty works of travel writing, novels, stories and poetry.

The most successful of his books is « Kumewawa – the son of jungle » (originally written in Esperanto) translated into 22 languages. In 1983 the Japanese ministry for education proclaimed in 1983 as one from the 4 best juvenile literature published in Japan. As a result, it appeared in Japanese in 300.000 copies, probably the largest printing from an Esperanto-based document. In total, over a million copies of Kumewawa were printed throughout the world.

Tempest above Aconcagua was a book that appealed across generations and to all parts of the world. His stories won prizes of Belartaj Konkursoj[28] and his poetry, although sparse, is considered valuable and worth studying.

Works

editThe works of Tibor Sekelj, novels and recordings of his travels, contain interesting ethnographic observations. He also wrote guides and essays on Esperanto, the international language. The majority of his books were originally written in Esperanto, but were translated into many national languages. Tibor Sekelj is undoubtedly the most often translated Esperanto author.

Descriptions of travels

edit- Tempestad sobre el Aconcagua, novel about his expedition in the Argentinian massif of the Aconcagua, originally written in Spanish, Buenos Aires: Ediciones Peuser, 1944, 274 pages.

- Oluja na Aconcagui i godinu dana kasnije, Serbo-Croatian translation by Ivo Večeřina, Zagreb 1955, 183 pages.

- Burka na Aconcagui, Czech-Slovakian translation by Eduard V. Tvarožek, Martin: Osveta, 1958, 149 pages.

- Tempesto super Akonkagvo, translation in Esperanto by Enio Hugo Garrote, Belgrade: Serbio Esperanto-Ligo, 1959, 227 pages.

- Por tierras de Indios, about the experiences of the author under the Indians in Brazil, originally written in Spanish, 1946.

- Durch Brasiliens Urwälder zu wilden Indianerstämmen, German translation by Rodolfo Simon, Zürich: Orell Füssli, 1950, 210 pages.

- Pralesmi Brazílie, tchec translation by Matilda V. Husárová, Martin: Osveta, 1956, 161 pages.

- V dezeli Indijancev po brazilskih rekah gozdovih, Slovenian translation by Peter Kovacic, Maribor: Zalozba obzorja Maribor, 1966, 252 pages.

- Tra lando de indianoj, translation in Esperanto by Ernesto Sonnenfeld, Malmö: Eldona Societo Esperanto, 1970, 186 pages.

- Excursión a los indios del Araguaia (Brasil), about the Indians Karajá and Javaé in Brazil, in Spanish, 1948.

- Nepalo malfermas la pordon, originally written in Esperanto, La Laguna: Régulo, 1959, 212 pages.

- Nepla otvara vrata, Serbian translation by Antonije Sekelj, Belgrad 1959, 212 pages.

- Window on Nepal, English translation by Marjorie Boulton, London: Robert Hale, 1959, 190 pages.

- Nepal odpira vrata, Slovenian translation by Boris Grabnar, Ljubljana: Mladinska knjiga, 1960, 212 pages.

- Ĝambo rafiki. La karavano de amikeco tra Afriko, originally written in Esperanto, Pise: Edistudio, 1991, 173 pages, ISBN 88-7036-041-5.

- Djambo rafiki. Pot karavane prijateljstva po Afriki, Slovenian translation by Tita Skerlj-Sojar, Ljubljana: Mladinska knjiga, 1965, 184 pages.

- Ridu per Esperanto, Zagreb 1973, 55 pages.

- Premiitaj kaj aliaj noveloj, seven short novels, originally written in Esperanto, Zagreb: Internacia Kultura Servo, 1974, 52 pages.

- Kumeŭaŭa, la filo de la ĝangalo, children's book about the life of Indians in Brazil, originally written in Esperanto.

- 1st edition Antwerp 1979.

- 2nd edition Rotterdam: UEA, 1994, 94 pages.

- Kumeuaua djungels son, Swedish translation by Leif Nordenstorm, Boden 1987, 68 pages.

- Kumevava, az őserdő fia, Hungarian translation by István Ertl, Budapest, 1988.

- Kumevava, syn ĝunhliv, Ukrainian translation by Nadija Hordijenko Andrianova, Kyiv, Veselka, 1989.

- Kumevava, sin prašume, Serbian translation, 2003.

- Kumewawa – Iben il-Ġungla, Maltese translation by Karmel Mallia, Rabat, 2010

- Mondo de travivaĵoj, autobiography and adventures throughout five continents. Pise: Edistudio, 1-a eldono 1981, 2-a eldono 1990, 284 pages, ISBN 88-7036-012-1.

- Neĝhomo, story about the life during an ascension Vienna: Pro Esperanto 1988, 20 pages.

- Kolektanto de ĉielarkoj, novels and poems, originally written in Esperanto, Pise: Edistudio, 1992, 117 pages, ISBN 88-7036-052-0.

- Temuĝino, la filo de la stepo, novel for the young, translated from Serbian by Tereza Kapista, Belgrade 1993, 68 pages, ISBN 86-901073-4-7.

Books about Esperanto

edit- La importancia del idioma internacional en la educacion para un mundo mejor, Mexico: Meksika Esperanto-Federacio, 1953, 13 pages.

- The international language Esperanto, common language for Africa, common language for the world, translated from Esperanto to English by John Christopher Wells, Rotterdam: UEA, 1962, 11 pages.

- Le problème linguistique au sein du mouvement des pays non alignés et la possibilité de le resoudre, Rotterdam: UEA, 1981, 16 pages (= Esperanto-dokumentoj 10).

- La lingva problemo de la Movado de Nealiancitaj Landoj – kaj gia ebla solvo, Rotterdam: UEA, 1981, 12 pages (= Esperanto-dokumentoj 13).

Manuals of Esperanto

edit- La trovita feliĉo, novel for children, Buenos Aires: Progreso, 1945.

- with Antonije Sekelj: Kurso de Esperanto, laŭ aŭdvida struktura metodo, 1960, 48 pages.

- with Antonije Sekelj: Dopisni tečaj Esperanta, Belgrad: Serba Esperanto-Ligo, 1960, 63 pages.

Works of ethnography

editDuring his travels in South America, Africa, Asia and Oceania he collected important ethnographic information which he gave to the Ethnographic Museum of Zagreb.

His principal ethnographic work is:

- Elpafu la sagon, el la buŝa poezio de la mondo (Pull out the arrow, about oral poetry of the world ), Roterdamo: UEA, 1983, 187 paĝoj, ISBN 92-9017-025-5 (= Serio Oriento-Okcidento 18),

where he presents translations of recordings he made during his travels.

Dictionary

editTibor Sekelj collaborated on a dictionary in 20 languages about museology, Dictionarium Museologicum, appearing in 1986. – ISBN 963-571-174-3

Notes and references

edit- ^ Tibor Sekelj. WorldCat. Retrieved 27 Oct 2024.

- ^ In regard to his nationality, Sekelj said that he was a world citizen with Yugoslav citizenship. He never emphasized his Hungarian citizenship although his parents were Hungarians, nor did he consider himself to be either Croatian or Serbian. That said, he lived in Croatia and Serbia for long periods as a Yugoslav (with a Yugoslav passport), though always with a declaration of being a world citizen.

- ^ http://esperanto.net/literaturo/roman/sekelj.html Information about Esperanto authors.

- ^ Universal Congress in Copenhagen and activity of EEU in the Blog of Zlatko Tišljar

- ^ Maybe was the last journey of the ship Teresa to South America because of the start of the world war. In 1939 the other ships that accustomed to travel to South America from Rijeka were used then of Italy because of the war in Africa. Deal about "Isarco", "Barbargo" and "Birmania" (all perished during the world war, and Teresa is taken by Brazil)

- ^ a b One or two years. He wrote « one » but said « two » during interview to Rukovet. « One year after the arrival in Buenos Aires, I already knew quite a lot the Spanish language for can start collaboration in some organ [...] », Sekelj T., Mondo de travivaĵoj, Edistudio, 1981, p15

- ^ a b In 40th years according to measure of Argentinian army one considered that Aconcagua was 7,021 m high. Sekelj mentions 6,980m. Of 1989 one considers that it is 6,962m

- ^ « At the beginning of 1953, when I arrived to Mexico, the sport of mountain climbing erupted. At that time in Mexico city there were a hundred mountaineer clubs with 25 000 members. In absence of any textbook for that sport, the Mexican mountaineers used my book about Aconcagua as a foundation for that sport. In the book I wrote everything that I'd learned on the ground, since the preparation for the expedition, we used the pickaxe, how to set up a tent, until the various kinds of avalanches and the impacts of the altitude sickness. The book was published in Mexico and every Mexican mountaineer knew it. From that followed that everyone there considered me a mountain climbing master, and the members of every club wanted me to be their guest climber, especially on the most difficult climbs. In this way I climbed Popocatepetl, Iztaccihuatl and many other volcanoes, mountains and insulating rocks. So, I unwillingly became an expert mountaineer. », Sekelj T., Mondo de travivaĵoj, Edistudio, 1981, p20

- ^ Group picture before the Statue of Kala Bhairava with Tibor Sekelj, Founding assembly of Esperanto-Group in Kathmandu, 1957, Österreichische Nationalbibliothek ÖNB 8092775

- ^ Tibor Sekelj on the top of the Mount Kosciuszko, 1970 before the peak cross and Esperanto flag in hand, Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, ÖNB 7619469

- ^ a b Instituto por Oficialigo de Esperanto = Institution for Officialization of Esperanto

- ^ 50th PEN-Congress, Lugano 1987 Leon Maurice Anoma Kanie, Ivorian writer and ambassador, at table with the world traveler, investigator and Journalist Tibor Sekelj, defender of recognition of Esperanto as literary language, Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, ÖNB 7920556

- ^ According to disclosures of Erzsébet Sekelj.

- ^ WRITER, WORLD TRAVELER

- ^ Gravestone of Tibor Sekelj, Subotica 1988, Österreichische Nationalbibliothek ÖNB 7177179

- ^ According to available information, appeared only three editions, with colour cover and black-white content: the first 15 September 1943 (32 pages), the second 15 October (32 pages), and the double edition 3–4 (probably the last) month later, with only 16 pages.

- ^ *Trovanto: Geografia Revuo

- ^ Geografia Revuo, 1956

- ^ In response to a question by Spomenka Štimec in OKO regarding the number of original texts he had written, he was unsure.

- ^ Tibor mentioned that his books also were translated in Urdu and other Mid-Eastern languages, although that has yet to be proven. Certainly it is possible they were in fact published there, but it was impossible to track them down in those countries' libraries because of the Arab and Sanskrit scripts .

- ^ Interview with Tibor in Serbian organ Rukovet 5/1983 and list of archived materials related to Sekelj of Zagreb television

- ^ Tibor intended to donate his collection to the city (not at all to the museum, without finding here support for his notions and draft), and his widower and the city even signed contract about that. From that was nothing, so that ultimately part of the collection (entirely 733 objects) the widower donated to the museum in Senta (in the catalogue of the exhibition in Senta one mentions gift of 86 objects).

- ^ International Puppet Theatre Festival

- ^ Radio-interview with Stipan Milodanoviĉ: « Ja sam učio oko 25 jezika. Mnoge sam zaboravio jer ih nisam više koristio. Uspeo sam da zadržim kao svoju trajnu svojinu 9 jezika koje i sada govorim Tih 9 jezika nisu dovoljni za ceo svet, ali jedan dobar deo sveta mogu da obidjem.» http://www.ipernity.com/doc/fulmobojana/7066327/

- ^ Josip Pleadin, Bibliografia leksikono de kroatiaj esperantistoj, page 137 « in 8 lands » (but are not said in that)

- ^ What he said to Zlatko Tiŝlar, clarifies his position: "It may be that he sought to change the fabric of culture when he led Esperanto-courses in cities that never had them before. That said there is little concrete information about the exact places where he taught."

- ^ Curso fundamental de esperanto del maestro Tibor Sekelj para los países iberoamericanos, Mexico 1970, instituted the Youth Esperanto Association of Mexico; Kurso de Esperanto – laŭ aŭdvida struktura metodo (Course of Esperanto – according to audiovisual structural method) was issued in form of sheets since 1966 (later combined as complete material)

- ^ eo:Belartaj Konkursoj de UEA

Sources

edit- Tibor Sekelj, after Zamenhof the most important esperantist in the non-esperantist world, Zlatko Tišljar, Esperanto-Organ (UEA Rotterdam) June 2011, 104th year, nro 1248 (6), pages 124–125

- Tibor Sekelj, after Zamenhof the most important esperantist in the non-esperantist world, Zlatko Tišljar for the Pantheon of www.edukado.net

- Interviews appearing in MATICA and OKO in 1987

- based on automatic translation from eo:Tibor Sekelj with vikitradukilo / Apertium

External links

edit- Additional information about Tibor Sekelj (in Esperanto)

- Books of and about Tibor Sekelj in Collections for Constructed Languages and Esperantomuzeum (de), (in English)

- Palm Tree Falls At Midnight (A short story by Tibor Sekelj, in Serbian language)

- Faces: The world traveler that returned, Spomenka Štimec, 27 November 2011

- Kumewawa: Iben il-Gungla/Kumewawa: Son of the Jungle by Tibor Sekelj, translated into Maltese by Karmenu Mallia.